The Dog Days of Summer

An old dog, a new puppy, paralysis and growth

At the end of June, a stray puppy turned up in our shared garden. He was about five months old, starving and dirty and terrified. At any human approach he would try to hide, crawling behind the thickest bushes and making himself as small as possible.

My neighbor and I coaxed him out with some improvised food, and I contacted the two rescue facilities in the area to see if they could take him.

I was not at all surprised when the answers came back in the negative. There are always many more stray dogs here in Mexico than there are homes.

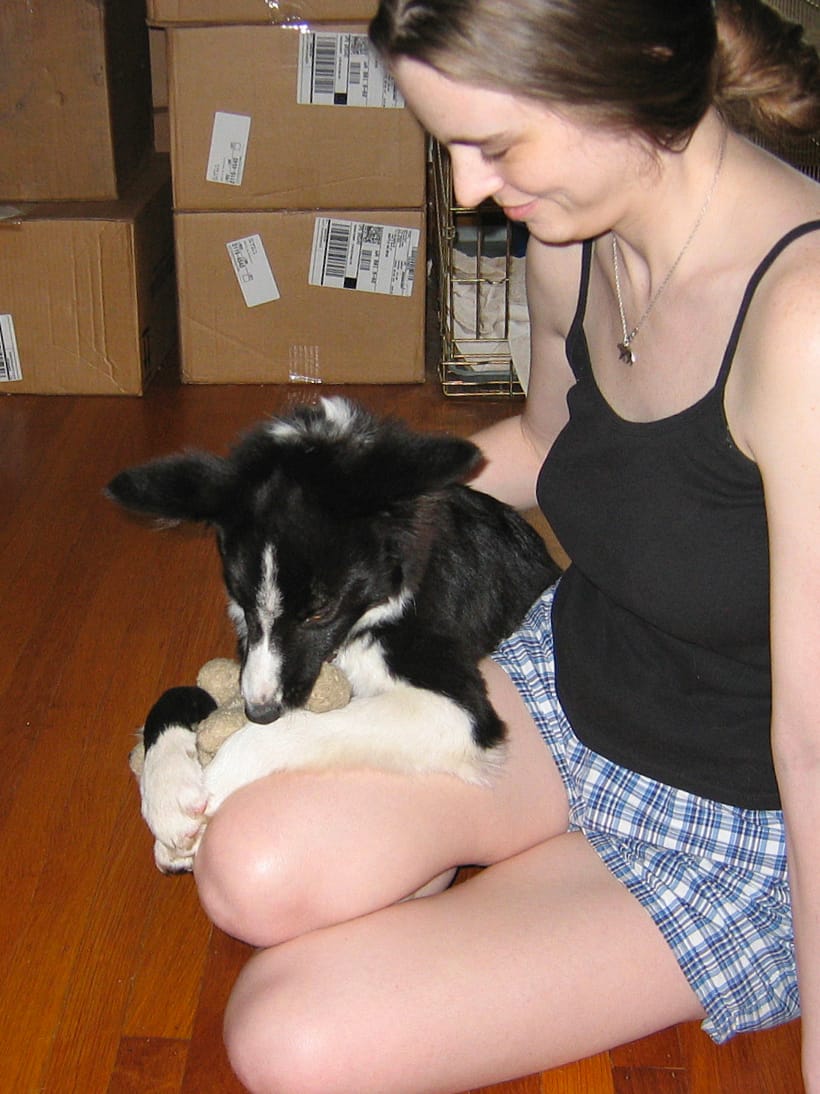

We’ve been a cat-only household for over six years, though my partner Jak and I owned a dog together once before. In 2005, at my instigation, we adopted a several-months-old border collie rescue; we brought her, along with two cats, with us from the US to Mexico in 2013. Tessa was an absolute sweetheart, smart and loving and (for her breed) surprisingly calm. I loved her very much.

Tessa died in 2017 at the age of twelve: one afternoon something went suddenly wrong with her spine, paralyzing her from the neck down. The vet here was unable to help her, and so we put her to sleep the next day.

I decided then that Jak and I would not ever adopt another dog — not because of Tessa’s death, but because I felt like we both failed her at the end of her life.

As the person who most wanted a dog in the first place, I had always been Tessa’s primary caregiver. I was the trainer, and I handled feeding, bathing, brushing, and clipping her coat and claws. Jak walked her sometimes and played with her when he felt like it, but I was the one who made sure she got enough exercise, and had enough toys, and wasn’t too bored.

About fifteen months before she died, I acquired a severely disabling autoimmune disease that left me physically unable to care for myself, much less a fifteen-kilo dog. My debility put a lot of new things on Jak’s plate, and seeing to the dog was not his priority. She never went hungry, and he still played with her on occasion; fortunately she was already elderly and did not require much activity. But the rest just … simply didn’t happen. Her coat got dirty and matted and her nails got too long and she went months at a time without a walk.

I was also distracted by my own pain and panic and depression, and didn’t focus mentally on Tessa’s care as much as I feel I should have. I noticed during her last couple of years that her legs had started to curve in a way that seemed odd, but I didn’t pursue an answer as intently or deeply as I otherwise would have. With the information I have now, I suspect that this was a sign of a long-term trace mineral deficiency. I have no factual reason to believe that this was related to the spinal problem she developed, but I have worried about it nonetheless.

Jak never shared my guilt or concern about Tessa; what I saw as lapses in her care didn’t even register with him. Even though this upsets me, I know that I am the outlier here, not him: compared to most people, my sense of duty regarding any person or animal in my care is emotionally intense, and my standards for nurture well above average (and honestly, only becoming higher over time). I’d helped raise Jak’s two kids after his divorce, and — in part because of the same disparity in styles and standards — I spent much of those eleven years begging him to pay more attention and take on more responsibility. It was a dynamic that I don’t have any wish to revisit.

Although I have had a partial recovery, I am still very much disabled. Cats need less physical care, and are small enough that I can do most of it myself if necessary. (The personalities of small dogs, like terriers and Chihuahuas, have never much appealed to me; I prefer the medium to large working and herding breeds.)

Dogs were my first great love when I was a child, and the knowledge that I would never have another made me sad, even though I felt it was the morally correct decision. Jak has suggested a few times in the years since that we might get another dog, but I always held firm: I couldn’t meet my own standards of care, and I knew he wouldn’t, so … a cat household we would be.

And then the universe dropped a puppy on our doorstep. A puppy who was abused and starving and had nowhere else to go.

Over the day and a half after the puppy’s first appearance, Jak and I had a series of serious conversations about the possibility of keeping him. By coincidence, I’d read something online the previous week that had triggered my grief over Tessa and our permanently dogless life, and my tears had led to a conversational retread of the reasons for that decision. I hadn’t been asking him to change anything, just explaining my sadness, but the past circumstances and the issues involved were very much in the forefront of Jak’s mind, as well as mine.

With the appearance of a very specific, needy dog, the equation changed. I laid out the specific commitments I needed from Jak if we were going to take on a dog:

- One, he needed to be willing to take full responsibility for walking him at least three times a week (as I am physically unable to do it), and equal responsibility for playtime, feeding, bathing, and other physical care. (I took on the primary responsibility for training and acquiring supplies, and full responsibility for diet and medicine.)

- Two, in the event that I become more disabled in the future than I am now, Jak would need to either take over all of the dog-related duties that I am unable to continue, or hire someone to do it for us. But we had to agree that devolution of care would not be an acceptable option.

This all added up to a serious imposition on Jak’s time … and his time is something he’s very protective of. So – though my friend’s response to the news of a stray puppy was “Congratulations on your new dog!” – our keeping him was actually far from certain.

I was emotionally prepared to not keep this puppy; I was not emotionally prepared to abandon him to the street. So while I waited for Jak to think it through, I quietly worried about what would happen in the event we couldn’t find him another home. Would my choices be between turning him out or putting him down?

Yet the next day, when Jak said we should keep the puppy and explicitly agreed to all my conditions, I didn’t immediately feel relief; instead I stopped and considered whether I could really trust him to follow through.

The answer to that question lies in another story: not about dogs, but about Jak and me.[1]

When I was thirty-seven, I briefly had decent health insurance through my day job, so I scheduled bone surgery on my left leg in an attempt to resolve the chronic knee pain that had plagued me since I was fifteen.[2]

For about ten days after the surgery, that leg was completely paralyzed from the hip down, so that ambulation meant pulling myself on crutches while dragging the dead leg behind me. Getting out of bed and across the hall to the bathroom on my own was an ordeal; getting all the way to the opposite end of the four-bedroom ranch-plan house and down several steps to the kitchen was a real problem. Never mind the question of what I would even be physically able to do (with only one working leg and my hands busy holding me up) when I got there.

Fortunately I did not live alone; at the time Jak was spending most of his time in our office one room down the hall, either writing or playing a video game. If I needed something — food, water, other physical assistance — he would be right there to help me.

Or so I thought. On that first day home, when I called out for him, he yelled back, “Just a minute.” I could hear the irritation in his voice at my interruption, and since it wasn’t an emergency, I set myself to be patient. But as the minutes ticked by, I started to wonder if he had … forgotten me? Was that possible?

I waited exactly half an hour, then called out again. “I’m busy!” he snapped back. “Just wait a minute!” As though it hadn’t been thirty already.

We’d been living together for about six years at this point. Jak had always been protective of his time outside of his day job, and tended to be resentful of anything that impinged upon it — that part was no surprise. I just had expected that, during the period of pain and increased disability after my surgery, his resistance to claims on his time would be superseded by concern for me.

Demonstrably, it was not.

Another thirty minutes passed with no movement from the next room, while I grew increasingly upset and anxious. It wasn’t that I was literally about to expire from hunger or thirst (although I wasn’t able to swallow my painkillers without liquid, so that was increasingly a problem), but the helplessness began to do a number on me emotionally, as I realized that I could not rely on my partner for assistance.

I grew up an only child of two abusive parents, so I have feelings about not being able to trust your family to take care of you. Not since I was a toddler had I been as physically incapacitated as I was after my leg surgery, and I was scared. What would happen to me if I couldn’t take care of myself?

And more, why would anyone ever let another person (whom they professed to love!) sit in pain and hunger and thirst when they’re asking for help, just because it wasn’t an optimally convenient time? Apparently my spouse considered my basic physical needs less important than whatever he most wanted to be doing. I was appalled, and deeply hurt.

After a week and a half, the nerves in my leg started working again; I had to wear a full hip-to-ankle articulated brace, but I was able to ditch the crutches, free up my hands, and ambulate under my own power.

The emotional problem was not resolved nearly so quickly. It was a thing that I talked about in joint counseling and in more than one long, tearful, late-night conversation. As usual when I brought up a significant issue with something Jak had said or done, he began by digging in and defending his actions. But as often happened, as we talked about it over time, he came around. He apologized, and he promised to be more caring and considerate in the future.

I called them my “tiny dino arms”, because they were about as mobile and useful as a T. Rex’s.

That promise wasn’t really put to the test for almost a decade, until in the spring of 2016 I began experiencing a slow-onset attack of Parsonage Turner Syndrome, an autoimmune disease where the brachial plexus — the nerve system that controls everything from shoulders to fingertips — first flares up into unimaginable pain, and then ceases to function altogether. Usually it only affects one side or the other, but I was in the unlucky percentage with a bilateral attack.

The flare left both my arms paralyzed from shoulders to elbows, and while I could still mostly control my hands and forearms, they were weak: I couldn’t even lift a coffee mug one-handed. I called them my “tiny dino arms”, because they were about as mobile and useful as a T. Rex’s.

We moved to Mexico so that we could save money for retirement, a plan that was in part dependent upon not hiring out any task that one of us could do ourselves. But Jak couldn’t reasonably do all of my work on top of his own. We hired a housekeeper to take over basic cleaning, and we started getting more takeout meals.

But when it came to caring for my person, that was all on Jak. I could manage to feed myself (hunching over and ducking my head down to meet my hands), but Jak had to shower me, and wash my hair, and learn to brush out tangles and make a ponytail. He brought me things and lifted things for me and scratched parts of my body I couldn’t reach, dozens of times a day.

He also took over many other things I’d been doing, like all the laundry, and making the raw food mix for our cats. There was no delivery of any kind in our part of Mexico in 2016, not even Amazon, so he had to do all the grocery shopping and errands, plus the extra trips to doctors[3] and physical therapy and — because all of this was really hard on both of us — weekly counseling.

I often hear it said that “People don’t change,” but nothing could be farther from my own experience.

And if he didn’t pick up the slack on caring for Tessa, well, that was as much on me as on him. I was too grateful for his other efforts and sympathetic to the difficulty of his position to ask him to do still more. And I was too anxious about money, and the extra expenses resulting from my illness, to suggest that we spend even more of it on dog walkers and groomers. (That, at least, is a choice I could make differently in future.)

Overwhelmingly, Jak’s reaction to my illness was sympathy and kindness. Sometimes he was visibly and audibly stressed, but he was not inconsiderate or cruel. He massaged my painful nerves, was sympathetic to my sleep deprivation, encouraged me to keep living through all the terror and depression. Because the universe loves a pile-on, I was also simultaneously entering perimenopause, and he bore up under the resultant weird mood swings.

He was, in short, amazingly good to me during the most difficult year of my adult life. That experience finally quieted the deep panic that I’d carried ever since my leg surgery, the fear of being ignored and abandoned when I needed help most, and restored my trust in his care.

Would he follow through on his promise to care for a dog, even over and above his own ideas of what was necessary? I believed the answer was yes.

We named the puppy Tashi, a Tibetan word meaning ‘good fortune’.

I … may have forgotten how much work puppies are.

But also I think that Tessa was just a much easier puppy than Tashi has turned out to be. She had her moments of misbehavior — she was an inveterate food thief, for example — but in general she was gentle and tractable.

Whereas Tashi — once he fully got over his initial fear and trauma — has turned out to be boisterous, unruly, and downright defiant. Teaching Tessa bite inhibition was easy: a calm and firm “no bite”, with positive reinforcement, did the job in short order. But Tashi is largely unmoved by anyone’s disapproval, and his primary response to being thwarted or redirected is frustration and doubling down. Teaching him not to bite has been a battle — one I have been losing badly, with the bruises and ripped skirts to prove it.[4]

Also I’m fifty-three, not thirty-five, and — since I’m missing the use of various permanently denervated muscles in my back and shoulders — physically much weaker. Meanwhile, in eleven weeks Tashi has gone from less than five kilos to fifteen. He’s going to be a much bigger dog than Tessa, bigger than any of us guessed at the beginning — I was hoping for eighteen kilos; now I’m predicting around twenty-four. It’s been weeks since I was able to lift him, and he is now much too strong for me to control on leash when he’s excited and lunging.[5]

I’m working hard on positive behavior training with treats, hoping I can eventually get him to the point where he is reliable without the need for purely physical restraint, while crossing my fingers that as he approaches adulthood he will settle down. (He’s a generally happy dog now, and during the five minutes a day that he’s not trying to bully me into rough play, or harassing the cats, he is sweet and affectionate.)

I’ve spent probably close to a hundred hours so far researching puppy nutrition, creating a giant spreadsheet, and figuring out a custom BARF-style raw food plan from the subset of ingredients we can source locally. I have to refactor the amounts every week or so to keep up with his rapid growth, which is a lot of work. So is prepping his food — he’s now up to almost a kilo per day, with eleven different ingredients, not counting the homemade treats.

I know — most people are perfectly fine scooping their dog some kibble twice a day, and to them this probably sounds ridiculous. I did say my standards of care are high! But there will be no nutritional deficiencies this time around, if I can possibly help it.

Predictably enough, all this effort has dominated my life, postponing my novel progress by another few months. I am chafing at the delay, but fending off resentment by recalling that this was a choice I actively made, and for reasons I still believe in.

Only men are allowed and encouraged to assume that their time is their own; like many women, I have lived much of my life in the little bits left over.

Which is not to say that I don’t need to get better at protecting my own time: I absolutely do. The ‘invisible labor’ gap between me and Jak has diminished over the years, but mainly because I’ve requested that he do more, rather than because I’ve allowed myself to do less.

This is all very much about society’s gendered expectations: I was taught, in ways both subtle and direct, that putting my needs or desires in front of anyone else’s was the height of selfishness. Only men are allowed and encouraged to assume that their time is their own; like many women, I have lived much of my life in the little bits left over.

The advent of a puppy — who, like a toddler, requires constant supervision and extremely frequent attention — has made time much more zero-sum for us than it has been in years: Jak taking focused, uninterrupted hours to write means I can’t, and vice versa. It’s thrown into sharp relief the fact that he still feels a certain level of entitlement to his own time, while I fundamentally do not.

But I can also see Jak daily making a real effort to do a more equal share of the pet-related work than ever before, something that I very much appreciate. For my part, I’ve begun consciously observing the ways he sets boundaries around his writing time, and considering them as potential models for my own behavior.

Finding a fair division of time and labor is an ongoing mutual relationship project, requiring much communication and self-examination. I often hear it said that “People don’t change,” but nothing could be farther from my own experience. Sure, there are some aspects of any person that are functionally immutable. But I’ve made many major changes in service of Project Be A Better Person, and I’ve watched my partner do the same.

Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise: you can teach an old dog new tricks.

Tashi at about five months old, fetching a ball outside in all his adorable puppy clumsiness.

For those of you who don’t know us, please do not make the mistake of assuming the following incident is representative of our entire relationship, or Jak’s entire character. ↩︎

Despite every specialist telling me that my chronic knee pain was a mechanical problem, it was — still is — a neurological problem. The surgery, therefore, was completely useless, as were all of the doctors. This is a recurring pattern in my life. ↩︎

The doctors this time were worse than useless; they were actively harmful. Fortunately I was older and smarter, so I didn’t end up undergoing irrelevant spinal surgery. ↩︎

Jak — who is ten inches taller, almost twice my weight, and a lot stronger and louder — gets more natural respect than I do; Tashi is still unable to physically bully and corner him the way he’d started to do with me. But he is actually less likely to obey Jak’s commands, I think because I’ve spent more time working with him. ↩︎

Before anyone chimes in with suggestions: I have already purchased a sturdy front-clip halter; just waiting for it to arrive. ↩︎