Toward a Spiral of Sound

Changing people’s opinions is hard. There’s a better way.

You want to change the world, but too often it seems hopeless.

If you agree with the above sentence, I can say with a high degree of certainty that you hail from the left end of our political spectrum. Not just because the political power in America this election cycle rests largely with the conservative party, but because for liberals, the desire to change things is almost definitional.

From social science we know that liberals and conservatives (note that here and elsewhere ‘liberals’ includes everyone on the left, from near-centrists to radicals, just as ‘conservatives’ includes everyone on the right) have distinctly quantifiable differences in moral values. Liberals focus primarily on caring and fairness, while conservatives consider loyalty, authority, and purity to be paramount. NYU professor Jonathan Haidt, who studies the psychology of morality, frames the distinction thus: “Liberals speak for the weak and oppressed; they want change and justice, even at the risk of chaos. Conservatives, on the other hand, speak for institutions and traditions; they want order, even at some cost to those at the bottom.”

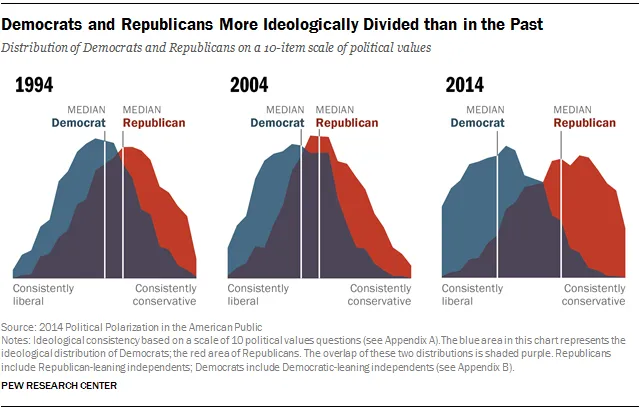

This fundamental divide is not new — John Stuart Mill called the order/reform dichotomy “commonplace” in 1859 — but if it feels like things have been getting more intense than usual in recent years, you are not wrong. The US Congress is more polarized today than it’s been in a hundred years (Senate) or ever (House), and the general American population is no less so.

Every indication is that this trend will only become more extreme over time, as the identified factors — from economic inequality to algorithmic filtering of social networks to gerrymandering — are all self-reinforcing.

As if that’s not depressing enough, social science has also shown that attempting to change people’s political opinions is almost always a doomed proposition. (Ezra Klein’s 2014 article “How Politics Makes Us Stupid” is a superb and fascinating look at these findings. You should definitely read it — go ahead, I’ll wait.)

In short, we tend to take on the ideologies that are popular within our tribe, and then cling obstinately to them. We do our best to avoid encountering contradicting facts, and if presented with one, we actively work to disbelieve it.

This tendency to dig in keeps us from angering and alienating the people we depend on for social, and sometimes economic, support. Our beliefs — political and religious — and our membership in our ‘tribe’ are crucial to our identities, and as Klein puts it, “changing your identity is a psychologically brutal process.”

So here we are: everyone’s doubling down on their identities, and therefore no one wants to question, much less change, their identity-critical beliefs.

But what if there were another option? What if we stopped trying to change people’s beliefs, and aimed instead at changing their behavior?

You might assume that people’s actions are directly reflective of their beliefs, but that is not the case; in fact our actions are strongly influenced by our assessment of social norms.

In the aftermath of World War II, psychologists “couldn’t explain the Holocaust by saying that x-many Germans had anti-Semitism just written on their hearts,” says Princeton professor Betsy Levy Paluck. “We had to explain it through the social context and the ways in which German citizens thought, ‘This is just what we’re doing now.’”

Paluck explains, “People are afraid to go against what they see as the prevailing norm, so they just don’t speak out. But their lack of speech then informs others, who take their silence to mean assent.” The result is what political scientists call ‘a spiral of silence’.

To illustrate this concept, let’s say you’re hanging out with a group of friends, and one of them makes a racist joke. If you’re like most people, you won’t leap to criticize your friend for his sense of humor; first you’ll look around at your other friends for clues as to whether they consider that sort of thing acceptable. They’re also looking at you and each other, wondering what everyone else thinks, and meanwhile no one is speaking out against racism. By the time someone finally changes the subject, everyone has gotten the impression that racist jokes are tolerated by this social group — even if privately, everyone besides the joke-teller felt that the joke was out of line.

And in fact, we know that a person who hears other people tell racist or sexist jokes afterward has an increased tolerance for racial or gender discrimination.

The good news is that the opposite can happen as well — call it a ‘spiral of sound’, if you will. We are watching one spiral of sound right now: every time another woman speaks out about harassment or abuse, it helps empower other women to speak in turn. “This is exactly how norms change,” said Paluck of the #MeToo movement.

Don’t let anyone tell you that marches and signs and protests don’t matter, that they don’t change anything, because science shows quite clearly that they do.

This opens another avenue for social influence: if you can reshape the perception of what is normal, you can alter behavior even before moving the needle on belief. You could, to continue with the previous example, create an atmosphere where no one would imagine telling a racist joke, even if some individuals continue to cling to racist attitudes.

That’s the thrust of Paluck’s research — a body of work that was impressive enough to bring her a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (aka ‘Genius Grant’) in 2017. “I’ve found several cases where our perceptions of what is normal may be more important [than individual attitude] for how we end up acting,” she says.

What if we stopped trying to change people’s beliefs, and aimed instead at changing their behavior?

Critically, the accuracy of a person’s perception of social norms is irrelevant; the subjective assessment is what drives their behavior. This assessment can be influenced by many things, including institutional cues, media reporting, and fictional narratives, as well as the behavior of other members of a person’s community.

And Americans are often very wrong about the opinions of their fellow citizens. For example, polls taken in 2014 showed 52% of Americans supporting same-sex marriage. Yet another 2014 poll which asked about perceptions of social norms — whether the answerer believed that a majority of Americans supported or opposed same-sex marriage — only 34% reported a belief in majority support.

More recently, a March 2018 study reports that “state legislative politicians from both parties dramatically overestimated their constituents’ support for conservative policies … a pattern consistent across methods, districts, and states.”

Let’s stop and think about that for a second. Our politicians broadly believe that Americans are ‘dramatically’ more conservative than we actually are. This might be in part because conservatives are significantly more likely than liberals both to contact their representatives and to vote.

It could also have a lot to do with the attention our professional news media has chosen to provide. When asked whether news outlets should be faulted for the disproportionate coverage afforded Donald Trump during the 2016 election, Paluck replied, “Giving someone all of that airtime informs people that [he’s] the popular choice, that people want to be watching him… Who gets the time matters.”

One year-long experimental study “analyzed a newspaper’s attempt to move community opinion and bring about policy change.” Their results showed that while a purposefully chosen news agenda had only an “extremely limited” ability to bring about changes in individual opinions, it had an “important effect” on people’s “perceptions of the dominant opinion climate within their communities.” The researchers concluded that news media could in fact indirectly bring about a desired change through shaping the perceived social norm.

“After the 2016 election many in the news media seemed all too ready to assume that Trumpism represented the real America, even though Hillary Clinton had won the popular vote,” laments economist Paul Krugman. “There have been hundreds if not thousands of stories about grizzled Trump supporters sitting in diners, purportedly showing the out-of-touchness of our cultural elite.”

So how out-of-touch are progressives really? What are the prevailing political and social values in America today?

When in 2016 journalist Roger Smith did a “deep dive into years of attitudinal polling results” from Pew, Gallup, and others, he found that “despite the right wing having cleverly and dishonestly sold the public on the idea that this is a ‘conservative’ country, the clear majority is most definitely progressive.” Pew’s broad 2017 Political Typology survey counts 51% of the general public as liberal, compared to 42% conservative.

In a companion post I’ve collected numbers from Pew and Gallup polls on major social and policy issues from the past two years. You can see that the liberal position has a clear majority in most cases, and a plurality in a few. The conservative position has a majority on none of the issues, and a plurality in only one question (under Racism).

These polls are important because they show that liberal Americans have the numbers to define the social norm. All we need to do is speak out — individually and en masse — about our beliefs.

You don’t need to convince anyone, or change anyone’s opinion — simply say, “Here I am and these are my values.” When enough people do that, public perception will shift; acceptable behavior will be redefined.

The Parkland kids have the right idea, and the organizers of the Women’s March. So too did Stormy Daniels, and the women who went public with accusations against Weinstein, and everyone who posted under #MeToo on social media.

It’s not hopeless. Don’t let anyone tell you that marches and signs and protests don’t matter, that they don’t change anything, because science shows quite clearly that they do.

In order for the United States to recover from this period of “incredible divisiveness and horrific speech and treatment of Americans,” says Betsy Levy Paluck, we need “strong messaging about what is considered appropriate speech and acceptable treatment of others.”

And, I would add, we need that message to be dominated by something other than Donald Trump’s Twitter feed.

Anything and everything you do to represent your values can help. Show up for a protest. Get a tattoo. Wear a progressive T-shirt to the grocery store. Tell your friend that his racist joke was not okay.

And share this article with your friends — that will help, too. Go make noise!

This essay originally appeared on Medium, but lives permanently in the Nine Lives archives.